Hello!

As it does every liturgical year, Lent has snuck up on me. You too? Probably, if it’s only recently hit you that Ash Wednesday is next week (February 22), thus beginning the long season.

“The liturgical traditions of the Church, all its cycles and services, exist, first of all, in order to help us recover the vision and the taste of that new life which we so easily lose and betray, so that we may repent and return to it.”

- Alexander Schmemann

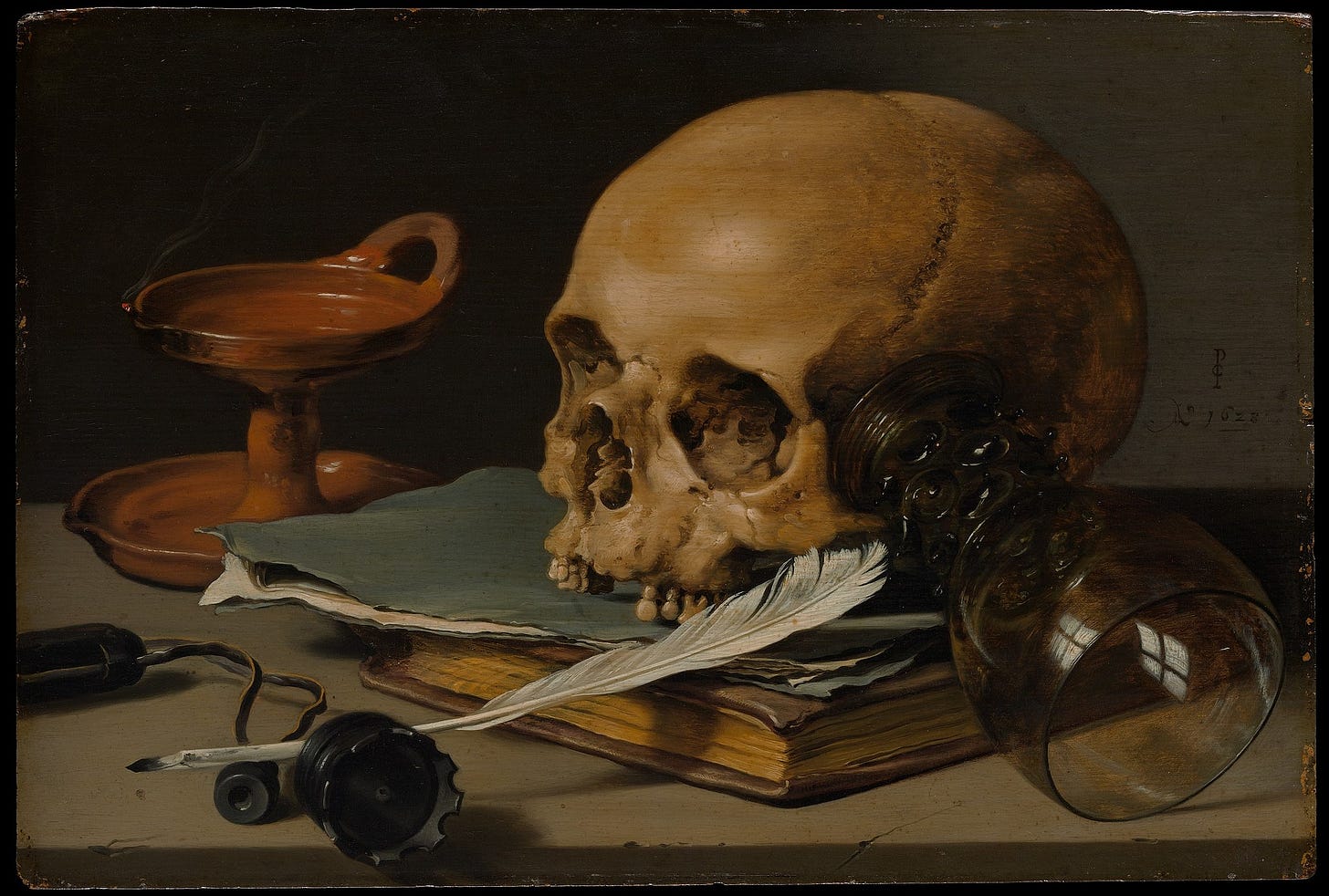

You may know that I released a Lenten book last year, having written the thing that I wanted but couldn’t find. Bitter & Sweet walks with you daily, giving you a short reading, a passage of Scripture, a daily meditation song, and a weekly work of art for reflection.

If you’re like me and didn’t grow up recognizing Lent, the idea of it may seem foreign — it may even seem borderline controversial, as though it’s focused on a works-based view of salvation. I understand where you’re coming from. I remember seeing the Catholic kids in high school with ashes crossed on their foreheads, talking about whatever it was they’d be giving up for the next few weeks, and it smelled of weird religiosity, an antiquated medieval practice of appeasing God with ritual.

Needless to say, I feel much, much differently now, and I’d even go as far to say that I actually look forward to Lent. That’s an unpopular posture, even among the most devoted of Catholics and other liturgically-minded Christians, but it’s true. I’ve reaped so many surprising benefits from participating in the ancient practice of sacrifice, prayer, and giving (the trifecta of Lent), not by doing any of it perfectly — not by a long shot — but in the joining of my temporary body and all its hangups and foibles with the eternal grace of Christ.

To avoid repeating myself, I thought I’d share with you a few short excerpts from the introduction of Bitter & Sweet, where I lay the groundwork for a Lent 101 briefing…

What’s Ash Wednesday?

The origins of Ash Wednesday are more recent but, ironically, less known, though the liturgical use of ashes is seen as early as the Old Testament as a symbol of mourning and penance. Jesus himself connected the idea of repentance with ashes,1 and various early church writings also indicate the continued use of ashes. Around the year 1000, an Anglo-Saxon priest named Aelfric said that, because we have examples in both the Old and New Testaments of the faithful symbolizing their repentance from sin with ashes, “Now let us do this little at the beginning of our Lent that we strew ashes upon our heads to signify that we ought to repent of our sins during the Lenten fast.”

On the forty-sixth day before Easter, always a Wednesday (because Easter is always a Sunday), many Christians recognize this start to Lent with ashes either sprinkled on their head or smudged as a cross on their forehead. As the priest or church leader does this, they say, “Remember that you are dust, and to dust you shall return.” Ashes symbolize both our repentant posture toward our sin and the temporal nature of our earthly bodies: we’re saying, this life on earth, fraught with the nature of sin, is not all there is.2

Wait… 46 Days?

Each Sunday during the season of Lent is seen as a short reprieve from Lent’s focus on fasting; these days could be seen as “mini Easters” of sorts. Yes, it’s still officially the Lenten season, but the Church sees it fit that we still frequently pause and recognize our already-here salvation due to Christ’s resurrection from the grave. On these Sundays, we relax from our penitential focus and rest the way we should on a sabbath. Thus, we could say the active observance of Lent lasts 40 days, while the entire season between Ash Wednesday and Easter lasts 46 days. Every seventh day, we cease from fasting.

Lent is Good For Us

Ultimately, we recognize the season of Lent before Easter not because God demands it of us, because Christ commanded it to prove our mettle, or because we must perfect ourselves before we’re worthy of Easter. We observe Lenten practices because they’re good for us.

Most of us are fine with an occasional indulgence of dessert, a pizza for dinner, or one late night out with little sleep. If we miss a day of exercise or drink a bit too much wine for a few days, our surprisingly resilient bodies will recover. The deliciousness of pizza and the enjoyment of an evening celebration with friends are a few delights of life, and God saw fit to create the world with bountiful opportunities for joy and occasional indulgence. But we know well what would happen if those indulgences were our mainstay, the normal daily practices of our ordinary life. Our bodies would drag with the effects of our choices: bloating, headache, sluggishness, crankiness, and worse. Keep it up, and eventually our bodies would become addicted to these excesses and let us know when they demanded more—always more, and more, until we tell it no.

These physical delights, which can so quickly spoil if overused, reflect the fragility of our souls as well; when we indulge our inner life with the sugars of laziness, complacency, or downright pride, our innermost self starts to atrophy. In his letter to the early Christians in Corinth, Paul writes to them, “Athletes exercise self-control in all things; they do it to receive a perishable wreath, but we an imperishable one. So I do not run aimlessly, nor do I box as though beating the air; but I punish my body and enslave it, so that after proclaiming to others I myself should not be disqualified.”3 Christ has not called us to a life of ease—we’re called to discipline.

As followers of Christ, if we’re athletes using our gifts, skills, and strengths to aim our lives toward an imperishable prize, a practice like Lent could be seen as a season of intense working out. Like Olympians before the worldwide games, we’re focused, determined, and ready to win the prize. Lent doesn’t earn our place in the game of life, but it makes us more ready for it. As one writer puts it, “It’s the spiritual equivalent of choosing to pick up the kettlebell instead of the Chex Mix, and it will have similar benefits to your soul.”4

In a world that celebrates indulging our whims whenever we want, it’s countercultural to practice the traditions of Lent. Welcoming the temporary suffering of Lent is swimming upstream in a culture that prefers to go with the flow. But as Chesterton quipped, to go against the current is to be alive. We can choose to live the paradoxical Christian life because we’ve been given new life in Christ, which gives us the faith, hope, and strength to do so.

If you’d like to participate in Lent but want some hand-holding, or if you’ve simply got a full plate and need something open-and-go accessible, consider getting a copy of Bitter & Sweet. It currently seems best-priced here.

In the next few weeks, I’ll share more of my thoughts about the Lenten practice of giving something up (along with adding something good), why I’ve framed Bitter & Sweet around the seven capital vices and their corresponding virtues, and my own experience as I walk through Lent 2023. If you’d like to join, I’ll be sharing this with paying subscribers of The Commonplace, which helps keep this newsletter going:

I hope you prayerfully consider participating in Lent this year — not to earn God’s love (never!), but to remind yourself of Christ’s never-ending grace.

Ora et Labora,

Tsh

“A dead thing can go with the stream, but only a living thing can go against it.” - G.K. Chesterton

Matthew 11:21

Aelfric’s Lives of the Saints

1 Corinthians 9:25-27

“What to Do for Lent—Ideas Based on the Three Pillars of Lent,” Green Catholic Burrow, February 9, 2018.