I’ve been thinking about this idea for a few weeks now.

As a parent of adolescents, as well as a teacher of them, I’m around this bourgeoning class of Gen-Z all the time. I love it, for the most part. They are funny and insightful, witty and thoughtful (if not yet wise, though not of their own fault). I agree with my friend here that I’m admittedly more at home parenting this age of children than I was with toddlers and preschoolers, even though the stakes often feel so high I quiver to my knees. Teenagers1, for the most part, are enjoyable to raise.

Yet the stats in the linked piece above, from knowledgeable and reputable Jonathan Haidt, are real and they also feel real to me. There is a growing idea among this age, especially with girls, that life is hard and this hard causes lots of mental health problems. These kids are seedlings growing in soil mired in fertilizer that espouses a belief that anxiety, depression, and their cousins are inevitable, unavoidable, and expected. Furthermore, many adolescents actively seek out these conditions, giving alphabet labels to their mental foibles because that’s just what one does in the twenty-first century. To not have a diagnosed (self or professional, it almost doesn’t matter) mental health condition is out of the ordinary, and so to feel normal, it’s natural to want a thing we can point to as to why we are not okay.

Before you throw stones at me: I have diagnosed clinical depression. My daughter has two mental health diagnoses. We have both been to therapy, and we both take prescribed medication as well as supplements. One of my sons has two diagnoses, both of which place him in the neuro-atypical crowd. We’re not above this, and I’m also very glad for scientific and medical advancement that allows us to explain and find help for these things. I am 100 percent on board with legitimate mental help, and I think most of us could benefit from reputable therapy at some point in our lives.

But I also believe that we swim in a worldview that chalks up “hard” with “bad,” and when you’re also forming tons of neuro pathways and hormones at full throttle while swimming in this culture, it’s understandable why life’s challenges might simply feel impossible without pointing to a reason why you’re not perfectly up to the task of tackling said challenges.

What if life is simply indeed often hard, we were never promised it would be easy, the journey of life is learning how to be fully who we were made to be, and life’s challenges are the primary tools for shaping us into that person?

Some of those challenges might definitely be legitimate health conditions, yes. Undoubtedly. But they may also be normal human milieus, such as a propensity to prefer the easy road over the difficult, a longing for community, a desire for meaning and purpose, and a need to be noticed and appreciated. The hard stuff could also be our vices, both universal and personal to us: our inclination toward pride, lust, envy, sloth, anger, greed, and gluttony. We all deal with grievous faults, and we always will this side of heaven.

In my role as an English teacher for the past five years, I’ve seen an increase in students’ excuses for not doing the hard work of reading old books and writing essays and stories, even though the challenge of this work hasn’t changed. A week doesn’t go by without an email landing in my inbox from a student explaining their reason for not getting work done on time (or at all) and in which that reason is something akin to anxiety, stress, depression, or feeling overwhelmed. These excuses are the thing that sends me closer and closer to feeling like Bart Simpson’s grandpa yelling at clouds, and I hear my own responses and wonder if I’m in the wrong for thinking what I think: Yes, my dear student…. Life is indeed hard. Do your damn work anyway.

Some of my colleagues and I will discuss this trend at school during our lunch break because we all notice it. We think about our grandparents who spent their childhoods during the Great Depression and their adolescence during World War II and wonder where all the grit has gone. When a particular student has told us — yet again, because she cites this source frequently — that she didn’t do the work because it triggers her anxiety to do so, we wonder aloud, “Would walking three miles to school every day in sole-worn shoes trigger your anxiety? Would rationing your weekly pantry staples so your family would have enough to make it to the next allotment keep you from doing your required work? Would waiting for orders from your commanding officer while in the trenches with your peers — orders that may definitely kill you — stress you out enough to simply not do what’s asked of you?”

I know exactly how this sounds. It’s “back in my day” but on hyperdrive, using the Greatest Generations’ unusual plight in history as the control group to point to when considering all variables. Our Boomer parents did it with us Gen-Xers, too, for sure. And I also get that our current batch of adolescents are growing up in a world that’s unusual: a pandemic that triggered lockdowns at the absolute wrong time in their development, screen addictions that both correlate with and cause a loneliness epidemic, inflation and rising college tuitions that truly don’t add up, and the like. I know. I do. There really is a mental health crisis among adolescents.

But that doesn’t change the fact that I’m legitimately concerned for this generation’s grit and their ability to handle the inevitable hardness of life. And I think Haidt’s conclusions are worth consideration: what if our culture’s approach to Cognitive Behavioral Therapy causes more adolescents’ mental health issues than it solves? As a quick 101, he says:

“In CBT you learn to recognize when your ruminations and automatic thinking patterns exemplify one or more of about a dozen ‘cognitive distortions,’ such as catastrophizing, black-and-white thinking, fortune telling, or emotional reasoning. Thinking in these ways causes depression, as well as being a symptom of depression. Breaking out of these painful distortions is a cure for depression.”

I have zero qualifications for expounding on the science behind CBT, as well as the data that points to cultural trends shifting to a rapid increase in mental health issues, so I won’t pretend to. Again, the entire article is worth reading. But what he says here stands out to me: that cognitive distortions both cause and are a symptom of depression, and breaking out of these distortions is a cure. Logically, this also means that the inverse is true: holding on to these cognitive distortions keeps us depressed.

Haidt goes on to explain that, in essence, the cultural trend points to current adolescents not only holding on to these cognitive distortions, but being told that these distortions are true (or at minimum, they’re not being told they’re untrue). What specific cognitive distortions? There are many and they come in all flavors, but Haidt and his colleague found these to be the most common:

1. What doesn’t kill you makes you weaker.

2. Always trust your feelings.

3. Life is a battle between good people and evil people.2

With my anecdotal evidence as a mom and teacher, I would also add other distortions like:

Life is supposed to be easy.

I am the only one who feels the way I do.

God is not for me.

When things are hard that means something is wrong.

I can’t make mistakes.

My worth equals my accomplishments.

…and so on.

I can’t help but acknowledge that every single human since the garden has wrestled with these lies, making these adolescents delightfully ordinary and not special — in the right way. These blatant lies our adolescents struggle with are common, and we know they’re not true — but it is true that our kids often really do believe them to be true. And it’s up to us, the wise adults in the room with them, to tell them they’re not true. It’s especially imperative these days because, again, evidence points to these kids growing in soil mired with a fertilizer of cognitive distortions. Their peers, the voices on TikTok, the zeitgeist of the moment, the entertainment industry, and even many of the established authority figures in their lives all often tell them that these lies are indeed true.

So what’s to be done?

Again, I acknowledge that mental health disorders are real, and a legitimate diagnosis for a legitimate disorder is a lifeline. So yes, get that help when it’s needed.

But I also believe we need to churn a different fertilizer into the soil and keep actively adding it, tending and pruning our seedlings, and not assume they’ll grow just fine because we did. As Haidt frequently points out, things have shifted in the culture, and things aren’t what they used to be, with just a different flavor of foibles. Our culture’s default is to believe cognitive distortions: hard is bad and what we feel is real.

So what’s in this fertilizer we need to actively mix into the soil? A few ingredients:

Daily specific acknowledgment of God as the source and summit of truth (yes, it’s a Sunday school answer, but there it is).

Weekly communal worship of God, even when there’s protest.

Regular family dinners around the table.

Collected and vocalized gratitude for ordinary goodness (meaning, written down and shared with others).

A delay in phone acquisition for as long as possible.

Proactive avoidance of social media for as long as possible.

A central parking lot at home for all devices, where they stay when they’re not in use and definitely overnight.

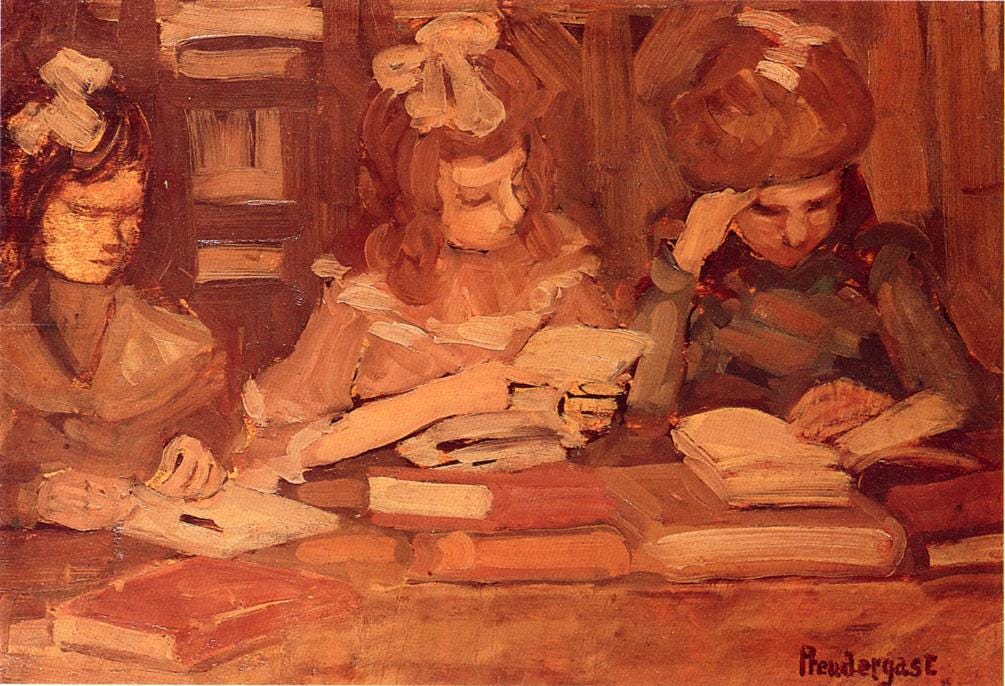

Reading aloud as a family.

Regular game nights (or some other shared screenless activity).

A home where adolescents are welcome to hang out (which usually means having food generously available).

Active, specific parental engagement in education, no matter where adolescents learn.

Required employment, even part-time or only during summers.

Low-stakes regular physical activity, such as evening walks.

Discussions of current events at home without villainizing sides or people.

Kindly, calmly, and firmly correcting adolescents when they’re wrong, without apology or hesitation.

Asking ordinary, frequent, non-confrontational questions about friends, beliefs, and the spending of time, big and small.

Prioritizing sleep, and making life changes for this when it’s necessary.

…And possibly most important, adults modeling all this in their own lives. Oof.

This list isn’t exhaustive or set in stone; it’s off the top of my head. And yes, these things individually seem trite or minute, almost insulting panaceas to real challenges like anxiety and overwhelm. But collectively and regularly, and over time, these ingredients really do change the soil in which we grow. In my own experience, practiced gratitude alone has been a game-changer. These ingredients aren’t easy, but they’re simple.

As concerned as I am for this generation’s grit, I do not think all is lost and I do not despair. One trend I see with both my children and students is an acknowledgment and awareness that this — all this we’re swimming in *gestures broadly* — is not how it should be. These adolescents are aware of their human propensity for screen addiction (arguably more than Boomers’ and Gen-X’s own awareness) and they want something better. They’re even starting to recognize their generations’ dependency on mental health diagnoses as a crutch for feeling special, realizing the danger of placing victimhood on a pedestal. More and more, the adolescents I interact with see this and want it to change. That alone gives me hope.

But they’re not yet wise, through no fault of their own, because wisdom is inherently born from experience — so it’s up to us adults to actively fertilize the soil in which they grow. We may not feel wise, and we ourselves may feel just as stuck in the same soil. We often are. Nonetheless, we must shake off the dirt and do the work anyway, because it is our job and we, too, were never promised life would be easy. Yes, my dear self…. Life is indeed hard. Do your damn work anyway.

Our kids are worth the work it takes to grow them in soil fertilized with virtue, wisdom, and grit. Let’s roll up our sleeves.

Ora et Labora,

Tsh

I actually despise the word ‘teenagers’ because it’s become shorthand for an age riddled with low expectations, even though it’s a relatively new word. Nonetheless, I use it because it’s understood. I prefer ‘adolescents.’

For more insight, I highly recommend reading his book The Coddling of the American Mind: How Good Intentions and Bad Ideas Are Setting Up a Generation for Failure, by Haidt and his co-author Greg Lukianoff

I want to have time for a more thoughtful response because this is such a powerful articulation of what my husband and I talk about re: our teenagers and their peers. Our family mental health history feels like it might be similar to yours and what I have found to be a PROFOUNDLY wise form of therapy is CBT's harder cousin: Dialectical Behavioral Therapy (DBT.) In many ways it is Life Skills 301 (not 101 because I find it quite advanced!) and it has very specific practices organized around: Mindfulness, Distress tolerance, Interpersonal effectiveness and Emotion regulation. Within each skill area there are a suite of specific tools - many with helpful and fun acronyms - that if practiced regularly would make us all better humans! Here's a helpful website that includes the tools/techniques: https://dialecticalbehaviortherapy.com/

All of this. You voiced the many scattered thoughts I've been meditating on the past six months here. I teach undergraduate students and have three kids (5, 8, 10), and everything you wrote resonates so deeply.