Why We're Required to Find Beauty

most especially when the world is aflame

A few weeks ago our family watched the last current episode of All Creatures Great and Small, having binged the two available seasons in the span of about three weeks (thankfully, they’re slated to produce at least two more seasons). I’ve also been listening to the audiobooks of James Herriot’s original memoirs upon which the PBS series is based, which have proved to be the ideal company for transplanting vegetables in the backyard garden, walking the dog through the neighborhood, and stirring dinner at the stovetop before we sit down as a family.

It admittedly feels strange to binge such an innocent, simplistic-in-plot, borderline saccharine-sweet storyline of a show, then catch up with the news on various parts of the world’s plight for their survival. To immerse myself in a true story about a humble farm animal vet driving through the idyllic Yorkshire Dales to treat sheep and cows, who then falls smitten with the town farm girl and comes home to a from-scratch meal from the live-in house help at the village vet clinic, feels almost too good to be true.

Sure, Dr. Herriot has his hands up the hindquarters of large animals in every episode (and in just about every story in the book), and he deals with the occasional unpleasant farmer, unpredictable weather, and capricious boss. But James isn’t currently battling a pandemic, massive social upheaval, or a literal war. (Yet. He does, eventually, as an RAF pilot in World War II, but that’s to come, most likely in season three.) He takes leisurely time in between vet appointments to pull his ramshackle car over to the side of the road and gaze unhurriedly at a sunrise or the slow grazing of sheep with their shepherd, and he sips cups of tea with his patients’ owners after an appointment with all the time in the world.

If I weren’t careful, I’d be tempted to feel guilty for so unabashedly enjoying a story whose main purpose is to remind me of the beauty of the world. Isn’t it wrong to enjoy beautiful things when there’s so much ugliness in the world?

That’s what we’re often told to believe. Why share on the internet the flower blooming in the sidewalk crack, the good book we just finished, or the funny exchange we had with our child because, by God, people are at war? Why hang art in our homes and water our backyard tomatoes when we have people a few miles away experiencing homelessness and food insecurity? Why are we commenting on something good when we haven’t yet said anything about the Terrible Topic Du Jour? Why read fiction when the non-fiction world burns?

In other words, why ever revel in beauty at all when there’s so much ugliness in the world?

At the height of World War II, writer C.S. Lewis was asked to weigh in on the question, “Why be so frivolous and selfish as to think about anything but the war?” As a veteran of World War I, he begins his answer with an anecdote he observed while enlisted: “Before I went to the last war I certainly expected that my life in the trenches would, in some mysterious sense, be all war. In fact, I found that the nearer you got to the front line, the less everyone spoke and thought of the Allied cause and the progress of the campaign.”

He then explains that he does, indeed, believe the current war to be of great importance: “I believe it to be a duty to participate in this war.” He next analogizes the Allied cause of World War II to that of rescuing a drowning man, and that if we’re personally not drowning, it’s our duty to learn lifesaving skills so as to be ready for when it’s our turn to save someone—that “it may be our duty to lose our own lives in saving him.” In other words, yes, we are called to care about our fellow human beings, and we may even need to sacrifice at great cost for the betterment of the world at large. But then Lewis says this:

“But if anyone devoted himself to lifesaving in the sense of giving it his total attention — so that he thought and spoke of nothing else and demanded the cessation of all other human activities until everyone had learned to swim — he would be a monomaniac. The rescue of drowning men is, then, a duty worth dying for, but not worth living for.” (emphasis mine)

To put it bluntly: the atrocities of our fallen world are worth dying for but they’re not worth living for. Far too often, our zeitgeist demands that we live for the abominations lest we appear uncaring at best, siding with the enemy at worst. We’ve forgotten beauty.

When we consume only things that remind us of horrors, be they war or famine or injustice, and be those items of consumption fiction or non-fiction, we may eventually forget that what makes them so awful is that they’re not meant to be. When we hop from one problem, to the next, to the next, with no pause to remember frequently (and to remind each other frequently) that the reason we long to eradicate such atrocities is so we can share with our fellow human beings the beauty that makes us drop to our knees, we make the world’s barbarism a near-idol and our outrage merely performative.

We long for there to be no war in no small part, though not exclusively, so that families can eat around their tables in peace, so that couples can fall in love and get married, so that peoples’ days can be about walking their dogs and pausing to watch the sunset instead of struggling to survive. These are things worth living for, and therefore, the lack of them might be worth us dying for.

But our constant focus on the world’s lack is not worth living for. It will kill us. It might very well be killing us now. I’d argue it’s one thing slowly strangling our current civilization.

Dostoevsky said that beauty will save the world, and this is what he meant, I believe. Not that one look at a rose in bloom will make everyone feel a-okay, but that those glimmers of a baby’s laugh, the trees in bloom in early spring, and the creak of a rocking chair on the back deck will remind us that this—all this hardship around us—is not all there is. We live in the shadows, and yet the sometimes seconds-long shimmers of beauty hint at the actual reality worth living for. We’re called to notice those shimmers if we want to live. It’s required.

So yes, I will continue to listen to All Creatures Great and Small while I dig in the garden, and we will continue to read The Hobbit aloud as a family while we dine at the dinner table. We will participate in the hard things of life and care deeply about those who have it infinitely worse than we do. We will also live as though there’s something good and alive worth living for, not live as though darkness and death are all there is, and shun the lie that if we enjoy anything good at all it must mean we’re choosing to live in oblivion. Quite the opposite.

As the sage prophet Samwise Gamgee once said, “There's some good in this world, Mr. Frodo, and it's worth fighting for.”

We must remember the good if we want to fight well. We must remind each other of the good as an anecdote to despair. We must relish in the beauty of the good so that we remember the realer-than-real reality.

My gracious, my heart needed this. Thank you, Tsh. Your voice is always one that reminds me there is always beauty to be found in the world.

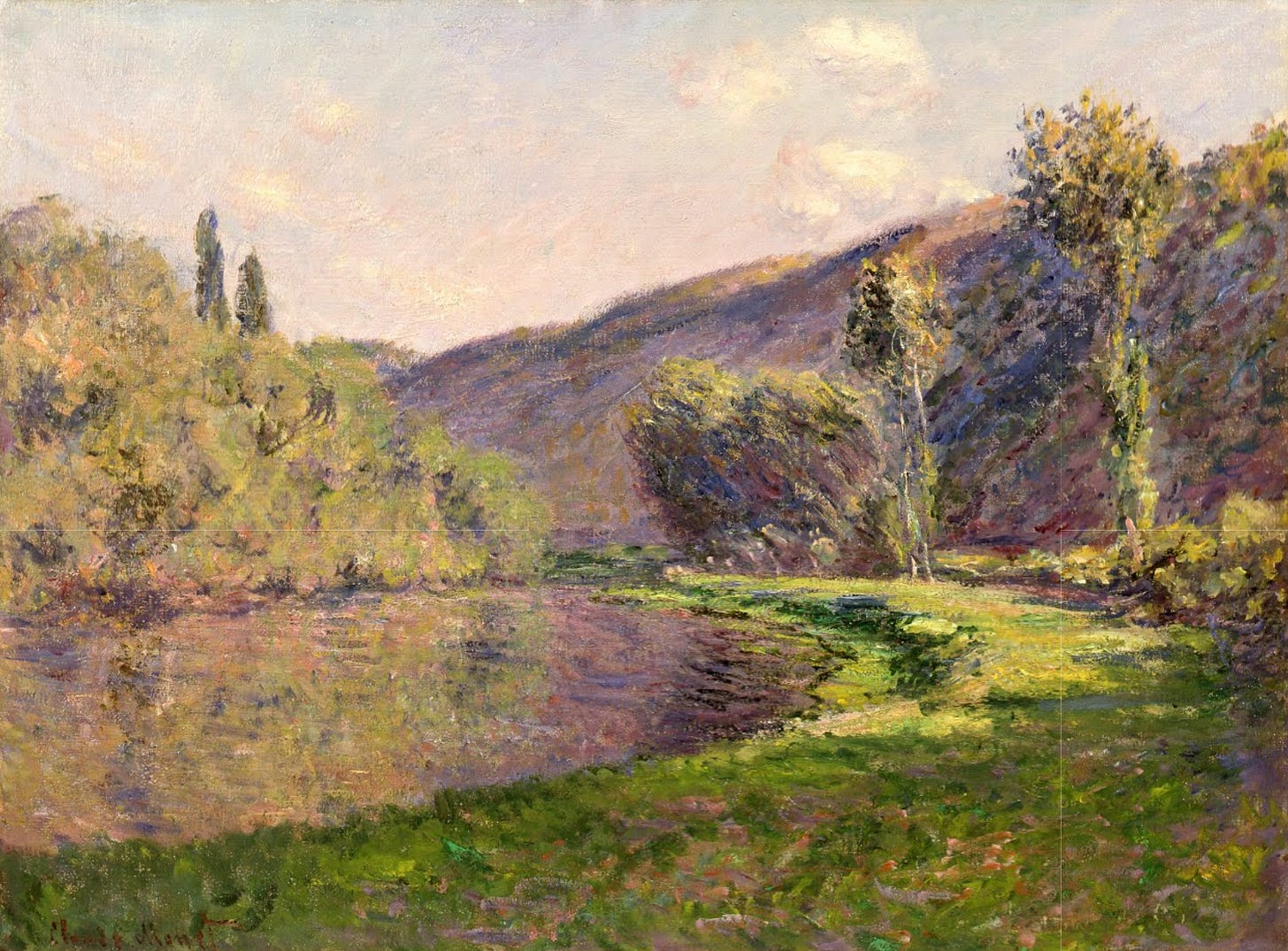

Yes, to everything you wrote. Your essay is one more voice continuing to press upon me the importance of beauty. I just finished Art Can Help by Robert Adams -- a book of essays about photos and paintings.

He wrote at the end of an essay about a photo by Wayne Gudmundson, "for many artists, beauty is the voice out of the whirlwind."

And, I think that's at the heart of your writing here too.